The Burney Family

Sold Christie’s London 1925

Bought A.L. Nicholson (dealer)

Private Collection USA

Christie’s New York 1996

Private Collection USA

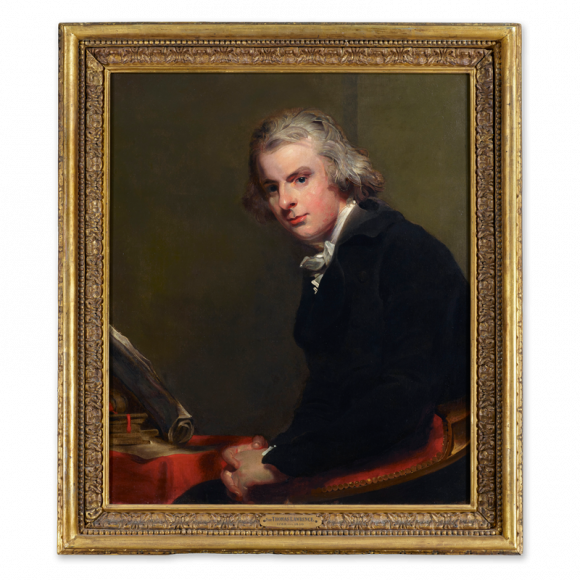

This superb portrait of the young lawyer Samuel Rose must rate as one of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s most engaging male half-lengths from the early part of his career.

Lawrence undoubtedly ranks as one of England’s very greatest portrait painters. Coming of age in the 1790s as the eighteenth-century masters of the genre - Reynolds, Gainsborough and Romney - began to fade, Lawrence found no equal in this country in the ensuing generation. The painter of choice of royalty, the aristocracy, the military and politicians, he progressed unrivalled through the Regency, the Waterloo years and the reign of George IV until his sudden death in 1830. From his very earliest years as a child he showed a precocious ability to draw. Indeed, he developed this into a commercial venture in his father’s coaching inn in Devizes before he was even 12 years old. Coming to London in 1787 at the age of eighteen, he set up in practice as a professional portrait painter in the capital. Three years later, after some early successes at the Royal Academy, he received a commission to paint Queen Charlotte. This now famous portrait - with its clever suggestion of movement, its unusually free and beautiful landscape backdrop, and its firework-like display of highlights in the Queen’s hair - cemented Lawrence’s reputation as the new exciting force in portraiture. He would never look back. Through associate membership of the Royal Academy to full membership, and finally to the presidency in 1820, his path had something of the inevitable about it. Further, after his commission from the Prince Regent in 1815 to paint the series of full-length portraits of the allied victors for the Waterloo Chamber at Windsor Castle, Lawrence’s reputation began to spread to the rest of Europe. By the end of his life he had not only outshone any other English portrait painter, but was holding his own with any portraitist on the European stage as well. And if we look for his worthy successors, it is not until the arrival of John Singer Sargent in England some 50 years later that Lawrence’s dazzling exercises with the human figure would be rivalled seriously again.

Samuel Rose (1767-1804) was a fascinating figure whose life was cut short by illness while he was still in his thirties. Of Scottish descent, he was educated at his father’s school in Kew and later at Glasgow University. He determined to follow a career in law. So he was entered as a student at Lincoln’s Inn in 1786, and called to the bar in 1796. His most famous case as a practising lawyer was the defence of the poet William Blake against a charge of high treason in January of 1804. Rose won this case after a vigorous cross-questioning of Blake’s accusers, two soldiers who claimed to have heard the poet blaspheming against the King. Rose was taken ill with a severe cold during the course of the trial, but he nevertheless managed to see it through to a successful conclusion. He never recovered from his illness, however, and he died of consumption at the end of 1804. Outside of the law, Rose struck up a firm friendship with the poet William Cowper (1731-1800), eventually acting as trustee for the royal pension of which the poet was in receipt. Importantly also it was Rose who made a point of bringing Thomas Lawrence to Cowper’s home in 1793, where the artist made his much engraved drawing of the poet (Private Collection). This action suggests a personal connection to Lawrence and it may also explain why Lawrence would paint Rose’s portrait some two years later. Rose’s promotion of Lawrence and the intimate nature of Rose’s portrait seem to hint at a genuine friendship between the two, rather than the usual artist/client relationship.

Whatever the nature of their relationship, Thomas Lawrence clearly found in Samuel Rose a sympathetic sitter. The artist poses his subject in a thoroughly original way, positioning Rose to the side of the canvas (at his desk) and directing Rose’s gaze from the centre of the canvas straight to the viewer. Through this device of close engagement, we in turn are drawn in to the picture. We feel as though we were ourselves present at a legal consultation; one where our case is being heard not just professionally, but quietly and even optimistically as well. If we examine Rose’s head close to, we can see Lawrence’s remarkable skills at first hand. Revealingly, we can see the artist’s pencil at work outlining the main bone-structure of the face. This is most noticeable in the area of Rose’s right eye, but also under his chin and in the edge of the collar of his coat. On close inspection this seems to confuse the eye and one wonders what Lawrence’s intention might have been in leaving the lines visible. But when we step back, much as one might step back from an impressionist painting, the whole picture comes into focus; this is clearly the distance at which the painter intended us to see the work. Lawrence’s treatment of the hair is also of the highest order. A skilful confection of differing shades and highlights gives Rose’s grey-powdered hair an extraordinarily life-like appearance. And even in the painting of the black coat – a notoriously difficult subject for artists - Lawrence excels. Rose’s coat is composed of not just a solid black swathe of paint, but a highlighted collar, subtle dark creases in the sleeve, and shadows from the lapel. The coat has luxurious form, such as few painters would be able to give it. Lawrence’s portrait of Samuel Rose is a quiet little masterpiece; an intriguing young sitter treated by one of England’s very great painters.

Note : Lawrence painted two versions of the Portrait of Samuel Rose. Some confusion has arisen about which one was which. Kenneth Garlick in his catalogue raisonne assumed there was only one and rather understandably conflated the provenances. On careful inspection of old images this can now be rectified.

In one version, Rose appears with wispier hair, a slightly fuller face and a slightly differing treatment to his cravat. The early provenance of this picture is unknown, but it appeared with Sotheby’s in 1961, where it was catalogued and sold as Hoppner. It was bought there by Agnews, re-attributed to Lawrence, lent to the Royal Academy’s 1961 exhibition Sir Thomas Lawrence P.R.A. and subsequently sold. It re-appeared on the market and sold at Christie’s in 2010, consigned by the executors of the late Lady King of Wartnaby. Garlick illustrated Rose’s entry in his catalogue raisonne with the image of this painting – an image presumably supplied by Agnews. However, his suppositions about its provenance prior to the Sotheby sale are incorrect.

By contrast this present version offered here is identical to an older photograph in the Witt Library, which shows it to have been the one sold at Christie’s in 1925 and bought by the dealer Nicholson. Christie’s in-house catalogue for that sale further shows it to have been consigned by the dealer Leggatt on behalf of a Miss Burney (Samuel Rose’s sister married Charles Burney). There is also a photograph - identical again to this present version - in the Heinz archive (National Portrait Gallery). This is annotated on the back by the same dealer Nicholson and has an accompanying letter from him to the art-historian William Roberts in 1926, in which he discusses it and another painting. Thus the ‘Burney Family – Christie’s – Nicholson’ part of Garlick’s provenance belongs properly to this version and not as Garlick states to the Agnew version. This current version then found its way to the United States, where it was latterly bought by Bagshawe Fine Art.